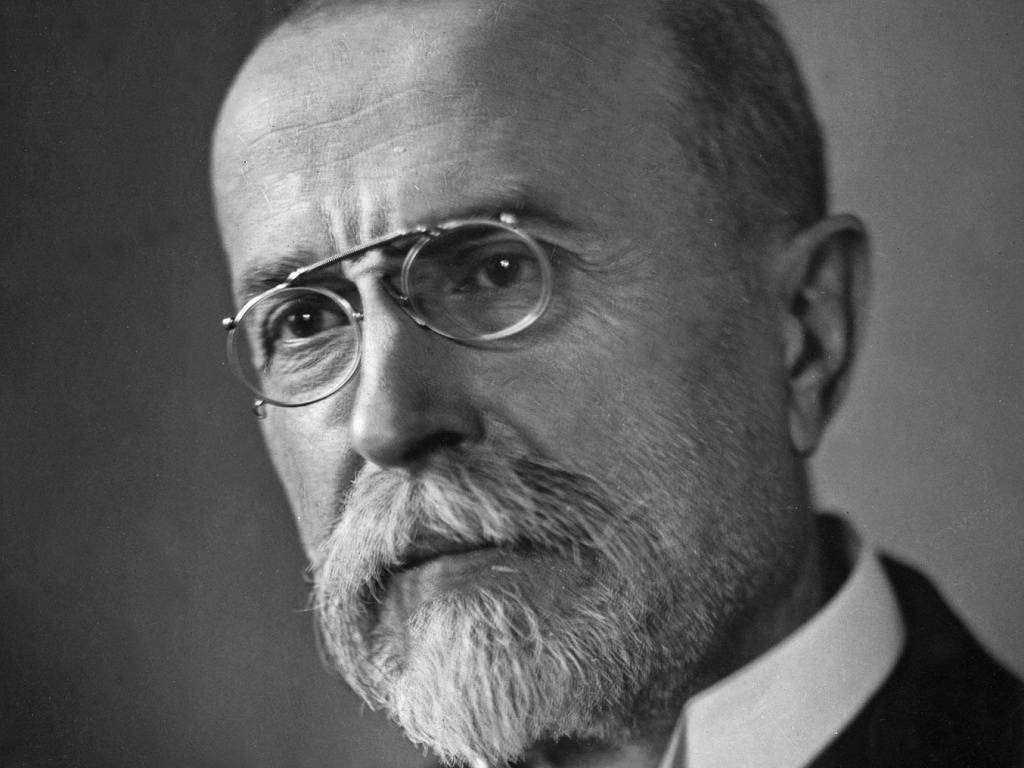

Are you interesting true WWII story about the Czech Resistance and a young woman’s role? If so, you will enjoy … And Give My Love to the Swallows, where you will learn about a woman from the past, one whom few remember and the young generation probably does not know at all. Resistance fighter Marie Kudeříková was a figure who did not escape history though. Instead, the Communists manipulated her life and made her a symbol of defiance against evil.

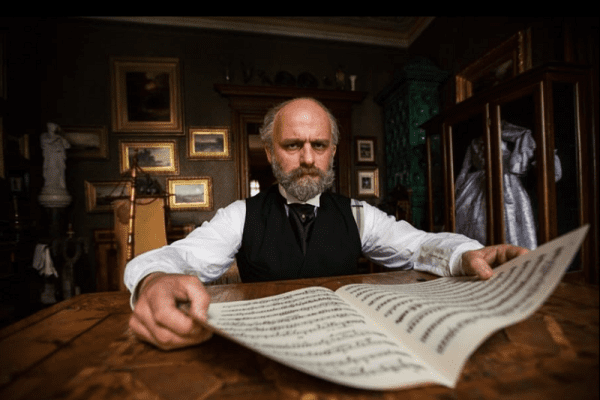

Today we are looking at a Czech film entitled And Give My Love to the Swallows (Czech: …a pozdravuji vlaštovky). It is a 1972 Czech biographical film based on the prison diary from Czech resistance fighter Marie Kuderíková.

The provided excerpt offers just a glimpse into the extensive article. To unlock the full content, become a Patreon patron. Our team meticulously gathers and curates valuable information, sparing you hours, days, or even months of research elsewhere. Our goal is to streamline your access to the best of our cultural heritage. However, a portion of the content is locked behind a Patreon subscription to help sustain our operations and ensure the continued quality of over 1,200 pages of our work.

Alternatively, you can contribute through Venmo, PayPal, or by sending cash, checks, money orders. Additionally, buying Kytka’s books is another way to show your support.

Your contribution is indispensable in sustaining our efforts and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage with you. Remember, your subscriptions and donations are vital to our continued existence.