At the time of the mass immigration of Czechs to America, in the midst of the 19th century (1), as Tomáš Čapek wrote, the first immigrants, as a rule, settled near seaside cities, near lakes and waterways and, later, also along the railroad lines. Thus, at the shore of the Atlantic Ocean, they formed colonies in New York, Baltimore, Boston, New Orleans, and Galveston, and on the shore of the Pacific Ocean, in San Francisco. (2)

Czech emigrants are waving from the S.S. President Harding, which landed in New York City on May 25, 1935. They later joined relatives in Ohio.

Near Lake Michigan, most Czechs settled in Chicago, Waukegan, Kenosha, Racine, Caledonia, Milwaukee, Sheboygan, Manitowoc, and Kewaunee. Near Lake Erie, they moved, above all, mostly to Cleveland and Detroit, near Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin, they stopped at Fond du Loc, Oshkosh, and Winnebago and near Lake Superior, at Duluth.

Along the rivers, the oldest settlements were in St. Louis, at the inlet of Missouri River to Mississippi River; in St. Paul, Minneapolis, Prairie du Chien, La Crosse, Dubuque, Clinton, Davenport, Muscatine, Burlington, Keokuk at the Mississippi River; in Cincinnati on Ohio River; Omaha on Missouri River, Cedar Rapids on the river of the same name; and in Fort Dodge, Moines and Ottumwa on Moines River.

After the arrival, every Czech immigrant had to challenge many of typical problems of immigrants, e.g., lack of money, lack of agricultural equipment, distant market, where they could sell or exchange their products, and there was no one they could turn to for help. (3)

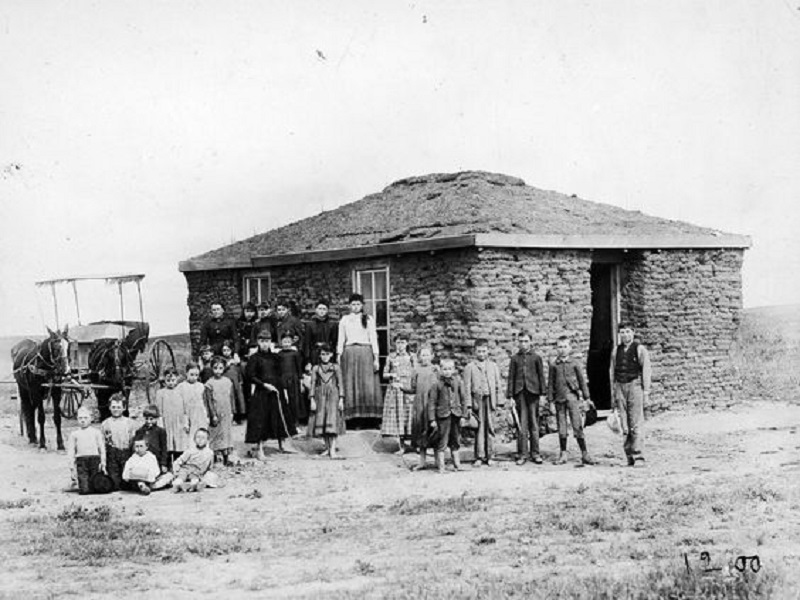

When Czech farmers settled on a prairie, in a treeless State, like Nebraska, they made their home in a ‘drnák,’ as they called them, which were initially just ‘dug-outs.’ They were built about four feet in the ground, by excavating that far. For the roof rafters, a few boards or poles placed over them and the hole was covered with sod. F. J. Sadílek, Register of Saline County in Nebraska, narrated how on a dark night he once rode with his horse and wagon right over a dugout, realizing his blunder only when he heard the terrified shrieks of the inmates. Frankly, these dwellings were mere burrows in the ground. Where the stream ran through the land, the settler usually dug himself into its slope.

Later on, sod dwellings were built above the ground, referred to as ‘sod houses,’ or ‘soddies’ for short.

Construction of a sod house involved cutting patches of sod in rectangles and piling them into walls. For windows, small holes were left in the walls, ‘pasted’ over, in place of glass, sometimes, with greasy paper and a larger opening was left for the door. The roof was the most difficult and dangerous part of the house to build. The lack of normal roofing materials, like wooden shingles or slate tiles, led to the inventive use of natural materials. A series of cedar poles held up layers of brush tied into bundles, mud, grass and sod. These roofs were a constant source of irritation and concern. Dirt or water, depending on the weather, fell from the ceiling most of the time. People hung muslin sheets from the ceiling to keep dirt from dropping into their food or an occasional snake from falling on to their bed. Roofs that became too wet sometimes collapsed. The resulting structure was a well-insulated ‘soddie’ but damp.

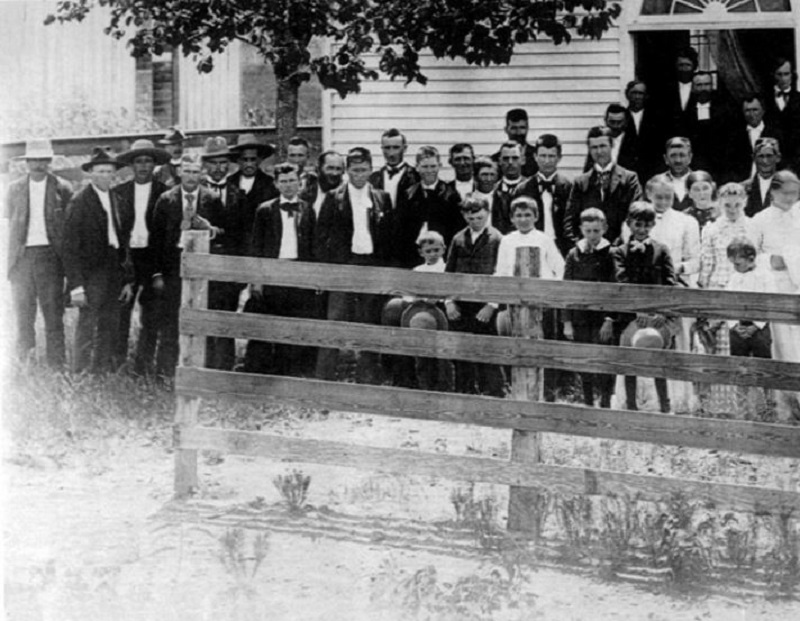

According to F. J. Sadilek, such sod dwellings “did not cost much; it only took some work.” It often took many weeks, especially if the settler’s nearest neighbors were too far away or unable to help. At first, schools and even churches were also constructed from sod. (4)

Circa 1891. Prairie Center Sod school house, District #57, in Custer County, Nebraska. Solomon D. Butcher Nebraska State Historical Society.

Josef Pecinovský came to Davenport, IA in 1854, and the following year, he went on foot, with his son, to Howard County, where Czechs began to settle, where he occupied 80 acres of land. He had to undergo all the distress and inconveniences, common to settlers, who found themselves on uncultivated land. “With hoes they broke up the ground for growing potatoes, and then built a dwelling, which was simple: a hole was dug, walled with sod, rafters were put over and covered with brush and then with a bundle of straw. The dwelling was thus finished. We slept on grass and straw. When we took care of the necessities, our two sons earned some money, which we badly needed and life went on.” (5)

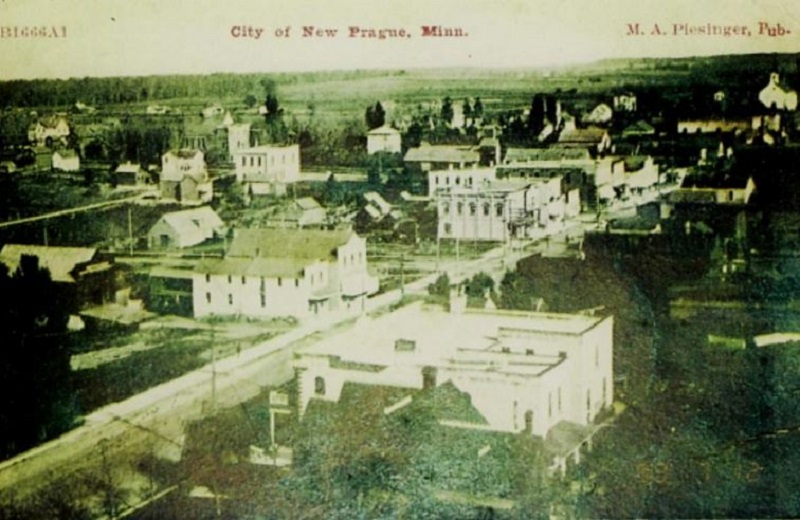

Jan Habenicht described the beginning is New Prague colony, MN in these words: “Let us imagine living in a tall thick forest, poor, with a few or even no dishes, with little or no supply of food, in a forest, where just wild beasts, especially bloodthirsty wolves, had their lairs, and where savage Indians, wishing the worst for the white men, turn up from time to time. Let us imagine that we should snatch nearly every inch of arable land with our blood-calloused hands, from such kind of jungle – and that was the situation for our first colonists.” (6)

There were no railroads at that period, the roads were poor, and if someone wanted to travel in the severe Siberian winter for a little flour, coffee or sugar to the mill or grocery, respectively, they had to harness their team of oxen to a primitive sleigh and to set out on a journey to the closest villages: Shakopee, Faribault, etc. The journey often took two to three days.

When Josef Klíma settled in the area of Prairie du Chien in Wisconsin, there was nothing but waste land. He had nothing for his livelihood but his hands, courage and endurance. Members of his family were put in a harness, as draught cattle, and pulled heavy logs to the place where they built their log cabin. The family lived long in poverty on cornbread and coffee made of roasted corn, but even this was not enough. With earnest hard work and frugality, Klíma saved enough that he could buy a team of oxen, wagon and a plough, which was easier to cultivate land than before, when he had nothing but a hoe.(7)

The farmers who settled in Caledonia, WI, had especially rough beginnings. Nobody would begin a journey without an axe, because even the road to Racine had not been cut through the forest. Ditches were bridged with beams, logs and branches, so that they could drive wagons over them. This was the method used to cover bogs and marshes. First they laid out long beams, over them the logs, next to one another, and then branches and brushwood. At that time there was nothing but dark virgin forest, full of marshes and bogs. And it was easy to lose one’s way. At first everyone cut and burned trees in the cold, in the heat, in the rain. During spring, they hoed the soil between the stumps and planted potatoes and sweet corn. In the early spring, while light frost still appeared, everybody cooked molasses from maples for sweetening coffee, made of roasted endive mixed with some roasted corn.

They preserved deer meat in hollow stumps, because they had no barrels. Those, who were lucky to have a team, from time to time they loaded a wagon with wood and took it to Racine, and when they received a dollar or a half a bag of flour, they happily sat on their wagon and drove home, loudly singing Czech folksongs. Harmony and sincere love prevailed among the first colonists. They would share the very last piece of bread and nobody would even think about cheating others. (8)

When Vojta Mašek arrived in Racine in 1861, Czech settlers worked in saw mills in the city and in winter made their living in a lumberyard. Those, who did not work in the saw mill, made shingles. Hardly anybody owned a yoke or a team. If they owned cattle, it was usually one cow or a calf. They burned beautiful maples, cut down and burned cherry trees and birches to gain arable land. The stumps were left in the ground till the roots rotted and they sowed in between.(9)

Characteristic was also the situation in Texas. Under most cruel and inhumane conditions, the Czech immigrants had to build their new dwellings, wooden shanties, from fell trees, floors from stamped soil, with a room in middle of which was a primitive fire pit for cooking. With bare hands they had to work their small fields, using the most primitive tools, which they themselves had to make. Ploughs were made of wood to which was attached a small piece of steel, which served to break up the soil. There being no way to sharpen the steel, it was not a very successful means for cultivating the crop. Beyond these hardships, the Czech immigrants had to defend themselves against Indian attacks, not to speak of unexpected natural disasters, such as grasshoppers.

In the cities, the situation was quite different. Whereas in the west the laborers and tradesmen could build homes, for which they were able to secure mortgages, the New Yorkers were forced to live in tenements, near the cigar shops, where they worked. The houses built in Chicago and Cleveland were initially from wood and it was possible to build them for a few hundred dollars. However the owners were bound with a yoke of repaying the mortgage to the builder, which forced them to deny themselves cultural needs and entertainment. The New Yorkers, having remained renting, did not suffer such wearisome experiences.

Americans, as Čapek wrote, loathed the immigrants, being unwilling to give them an overnight stay, in fear that they would bring in lice or other insects. At best, they let them sleep in a shed or in the stall. Some families, camped in shanties, put together from discarded wood and sheet-metal, on the land, presumably lacking a legitimate owner. These people were known as ‘squatters.’ Based on the reminiscences of Chicago chroniclers, Bohemian squatters, in 1852, spread to the city border, near the lake, and near the old cemetery, which was later attached to Lincoln Park. They apparently stayed in the boarded shanties until 1855, when the land owners chased them out.

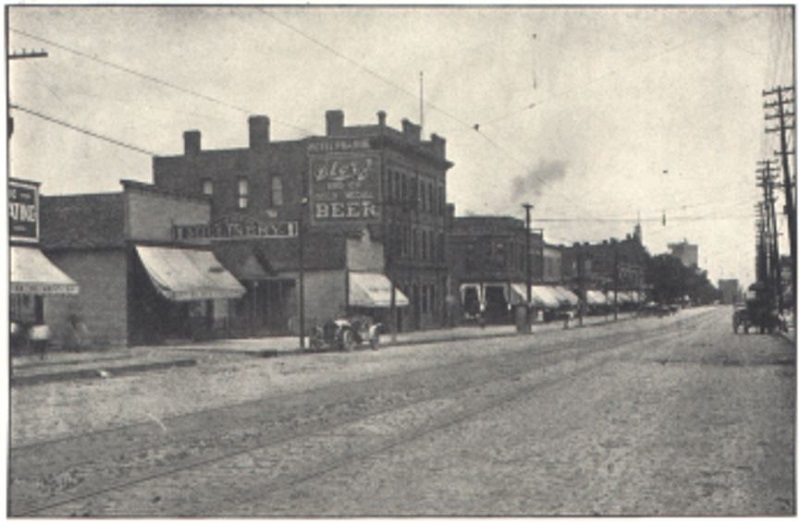

Whoever traveled to Omaha, NE, in the nineties of the 19th century, could still see groups of shanties joined together from fished-out wood, occupied by the Czech poor. In Minneapolis on the Mississippi River, near Washington Bridge, an abundant colony of shanty men had grown, which the Americans ridiculed by calling it ‘Bohemian Flats,’ otherwise known as ‘Little Bohemia.’ Those who lived there, allegedly, did not pay rent or taxes. (10)

As for the tenement houses on the Eastern side of New York, where in the early days, many Czech immigrants lived, there were real ‘dark rooms’, without air and without light. Where two houses stood on one lot, one facing the street and other the yard, the situation was even worse. The apartments in the back house were, usually, darker and gloomier. Only in the eighties and nineties, the New Yorkers, en masse, left the lower part of the city, and found new abodes, with the center on the 73rd Street and First Avenue. More modern houses were built, equipped with greater comfort and better hygiene.

In Chicago, sometimes, as many as four families lived in a small house and cooked on the same stove. The children and women gleaned firewood, with hampers on their back, along the railroad tracks. In slaughterhouses, the women would get free lungs, kidneys and chicken legs; otherwise it was thrown away, because the Americans did not eat animal viscera, which were sold for a penny. This is the way the families lived, until they found a job.

The climatic changes also posed problems for the settlers. Take for example the Great Plains, the area of the prairies, about which everything seems extreme. Summer brought endless days of heat, when the surface temperature could exceed 120 degrees. Periods of drought, rain storm, tornadoes, swarms of grasshoppers that could destroy fields of crops, and never ending winds, also challenged the settlers. Winters were long and cold. Blizzards were so strong that they could trap livestock and homesteaders under the snow. And then there were Indians, against whom the settlers had to defend themselves and the problems could go on and on.

To regress, it is astonishing that, when the Moravian Brethren immigrated to America, more than 100 years prior to the mass migration of Czechs to America, they did not experience such difficulties. Their emigration and settlement were well organized even before their arrival. They did not have to fear the attacks by the Indians, since, they, generally, befriended them. They lived in decent dwellings, starting with the log-cabin and soon building brick and stone-made buildings, some of which have been preserved to date. They also did not have to worry about employments, having all been trained as master tradesmen and artisans, before they came.

For more information about the various difficulties the homesteaders had to face, the reader will find in individual chapters covering various areas where the Czech immigrants settled.

Notes:

- Reminiscences of old settlers on this theme can be found in Kalendář Amerikán.

- Tomáš Čapek, Naše Amerika. Praha: Nákladem Národní rady československé v Praze, 1926.

- A. E. Benesh, Kalendář Amerikán, 47 (1924), pp. 288-299.

- F. J. Sadílek, Z mých vzpomínek na první doby ve Wilber. Omaha: Národní tiskárna, 1914.

- Josef Pecinovský, “Ze zkušenosti starých osadníků čských v Americe, Kalendář Amerikán, 14 (1891), pp. 192-94.

- Jan Habenicht, Dějiny Čechův Amerických. St. Louis: Tiskem a nákladem časopisu “Hlas”, 1910, pp 393-94.

- Josef Klima, “Ze zkušenosti starých usedlíků v Americe,” Kalendář Amerikán, 14 (1891), pp. 195-96.

- Jan Habenicht, Dějiny Čechův Amerických, op. cit., p. 457.

- Jan Habenicht, Ibid.

- A. J. Moncol, N. Y. Deník, 20.června 1923.

– – – – – – end of guest post.

(Images above added by TresBohemes.)

American author Willa Cather shared her images of Czech immigrants in her book, My Ántonia.

My Ántonia, published in 1918, is arguably the most famous work of American novelist Willa Cather. The novel takes the form of a fictional memoir written by Jim Burden about a Czech immigrant girl named Ántonia with whom he grew up in the American West. Cather, like her character Jim, moved to Nebraska when she was ten years old, and she bases many of the events, characters, and settings of the novel on her own childhood experiences.

My Ántonia is a great reminder that the stories of pioneering, heroic men would not have been possible without the strength of the women who stood beside them.

The text of this particular hardcover edition follows that of the 1918 edition, with minor emendations, added footnotes and new illustrations.

Guest Post Author

Mila Rechcígl

Miloslav Rechcígl, Jr. is one of the founders and past Presidents of many years of the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU), an international professional organization based in Washington, DC. He is a native of Mladá Boleslav, Czechoslovakia, who has lived in the US since 1950.

Read his entire profile here. Discover Mila’s many books on Amazon.

Thank you in advance for your support…

You could spend hours, days, weeks, and months finding some of this information yourselves. On this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

The strength and fortitude of these early settlers and pioneers is something I wish we had in the people of today. We’ve gotten complacent and lazy as a culture, and it is going to lead to our demise.

Amen. You said it well.

I don’t know how the people survived. They had strength and determination mixed with a toughness and grit. We can never forget how hard our ancestors fought for us.

They didn’t have it easy. All the troubles they had to go through just to get established in a new place. From crippling diseases to wagon accidents, dangerous weather, wild creatures, and attacks by Native Americans, life was very difficult for those early Czechs.